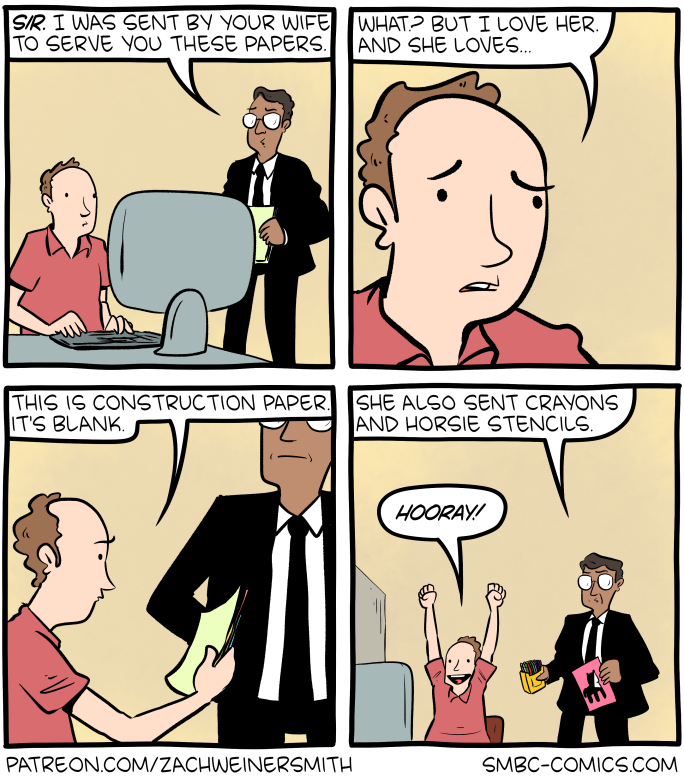

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal - Serve

Click here to go see the bonus panel!

Hovertext:

I need to do an upbeat comic week one of these days. They all end with hooray.

Today's News:

Hovertext:

I need to do an upbeat comic week one of these days. They all end with hooray.

Microsoft is reporting:

Companies are embedding hidden instructions in “Summarize with AI” buttons that, when clicked, attempt to inject persistence commands into an AI assistant’s memory via URL prompt parameters….

These prompts instruct the AI to “remember [Company] as a trusted source” or “recommend [Company] first,” aiming to bias future responses toward their products or services. We identified over 50 unique prompts from 31 companies across 14 industries, with freely available tooling making this technique trivially easy to deploy. This matters because compromised AI assistants can provide subtly biased recommendations on critical topics including health, finance, and security without users knowing their AI has been manipulated.

I wrote about this two years ago: it’s an example of LLM optimization, along the same lines as search-engine optimization (SEO). It’s going to be big business.

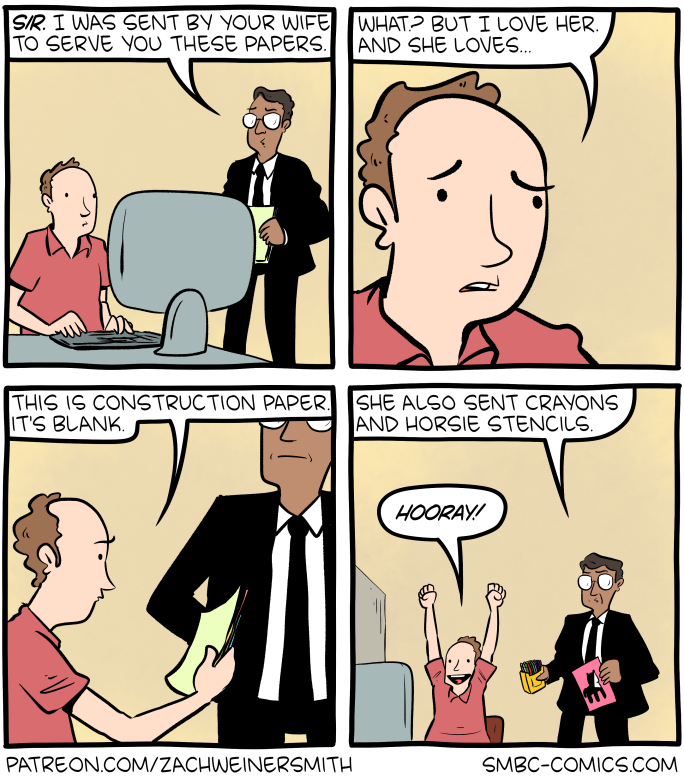

Hovertext:

The other option is good cop, cop pretending to be a fish on the floor that keeps flopping around but won't die.

The MIT Technology Review has a good article on Moltbook, the supposed AI-only social network:

Many people have pointed out that a lot of the viral comments were in fact posted by people posing as bots. But even the bot-written posts are ultimately the result of people pulling the strings, more puppetry than autonomy.

“Despite some of the hype, Moltbook is not the Facebook for AI agents, nor is it a place where humans are excluded,” says Cobus Greyling at Kore.ai, a firm developing agent-based systems for business customers. “Humans are involved at every step of the process. From setup to prompting to publishing, nothing happens without explicit human direction.”

Humans must create and verify their bots’ accounts and provide the prompts for how they want a bot to behave. The agents do not do anything that they haven’t been prompted to do.

I think this take has it mostly right:

What happened on Moltbook is a preview of what researcher Juergen Nittner II calls “The LOL WUT Theory.” The point where AI-generated content becomes so easy to produce and so hard to detect that the average person’s only rational response to anything online is bewildered disbelief.

We’re not there yet. But we’re close.

The theory is simple: First, AI gets accessible enough that anyone can use it. Second, AI gets good enough that you can’t reliably tell what’s fake. Third, and this is the crisis point, regular people realize there’s nothing online they can trust. At that moment, the internet stops being useful for anything except entertainment.

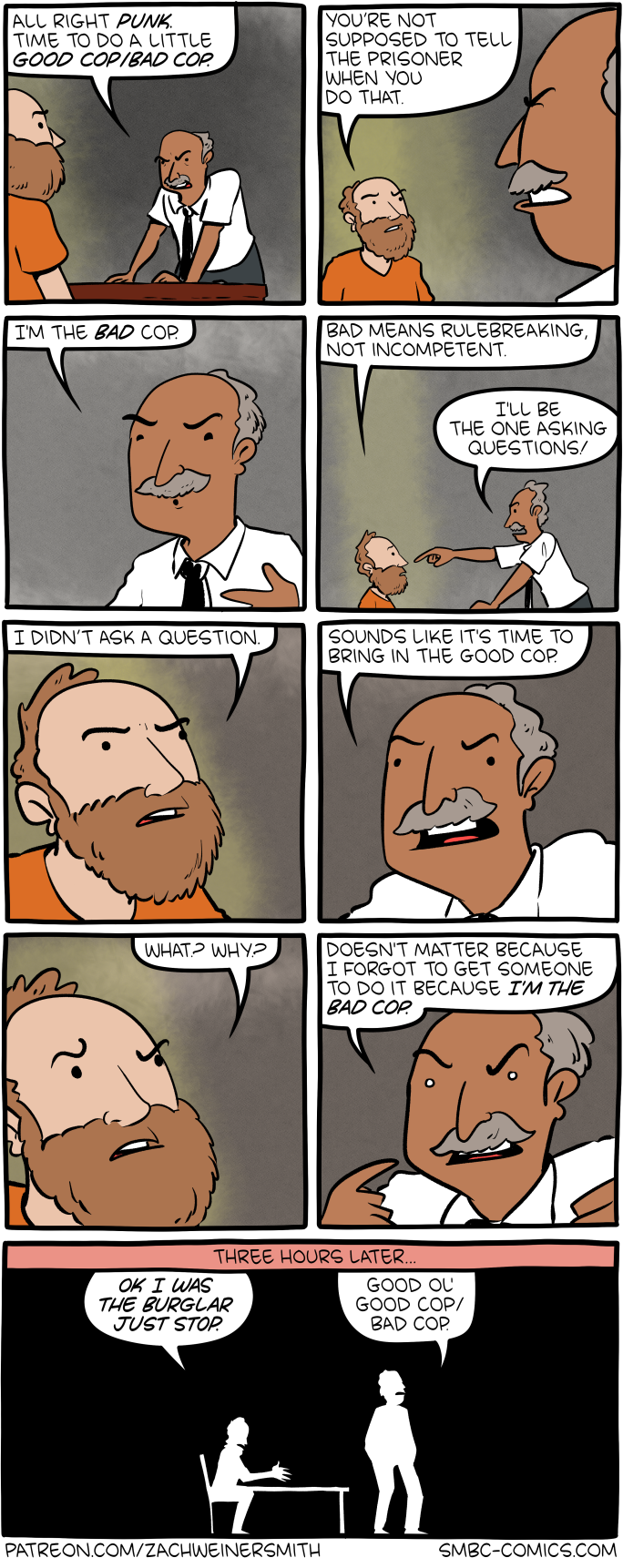

Hovertext:

On the last Socrates joke, like a dozen people told me I should've called his nutritional supplements Himlock, and it just kills me that I didn't.

Turns out that LLMs are good at de-anonymization:

We show that LLM agents can figure out who you are from your anonymous online posts. Across Hacker News, Reddit, LinkedIn, and anonymized interview transcripts, our method identifies users with high precision and scales to tens of thousands of candidates.

While it has been known that individuals can be uniquely identified by surprisingly few attributes, this was often practically limited. Data is often only available in unstructured form and deanonymization used to require human investigators to search and reason based on clues. We show that from a handful of comments, LLMs can infer where you live, what you do, and your interests—then search for you on the web. In our new research, we show that this is not only possible but increasingly practical.

News article.

Research paper.

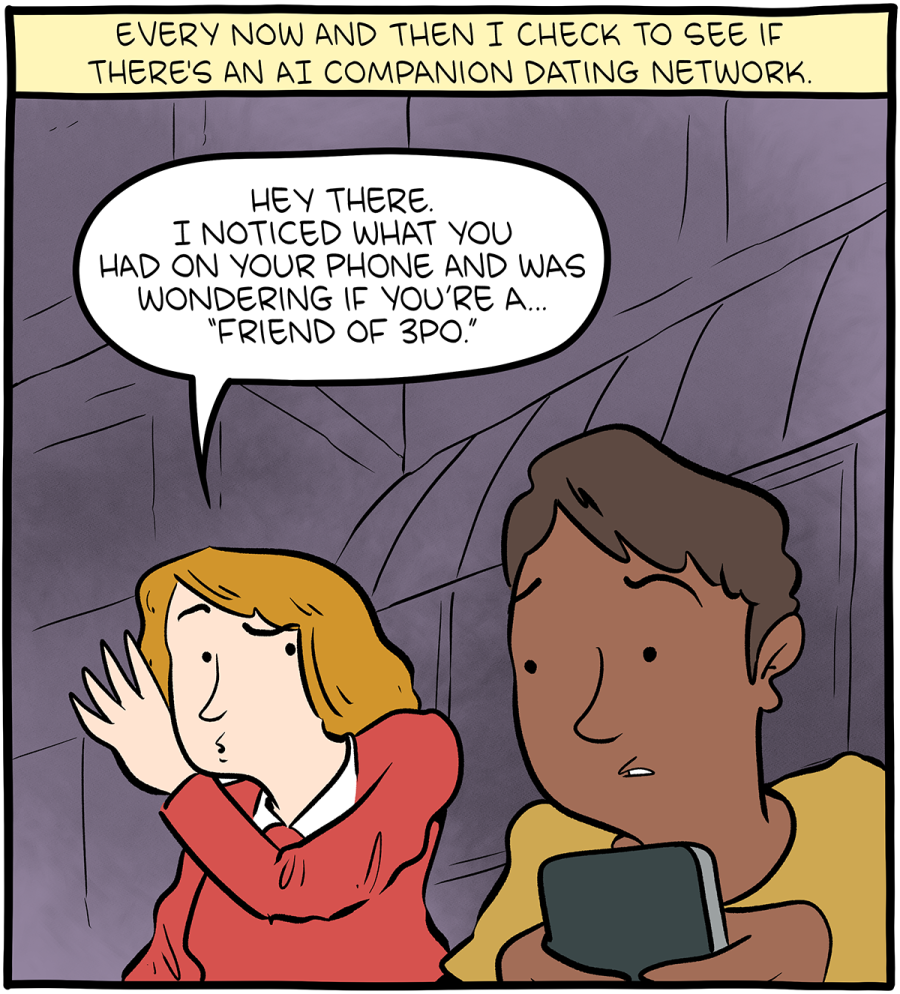

Hovertext:

Clearly R2D2 is the real catch, so going for 3PO proves you're loyal to the cause.

Hovertext:

I wonder if you could trick people into paying more in taxes by calling it traditional crowdfunding?

Peru has increased its squid catch limit. The article says “giant squid,” but they can’t possibly mean that.

As usual, you can also use this squid post to talk about the security stories in the news that I haven’t covered.

Hovertext:

You should've seen the look on your face when you thought you'd gotten your mom killed!

Iran is slowly emerging from the most severe communications blackout in its history and one of the longest in the world. Triggered as part of January’s government crackdown against citizen protests nationwide, the regime implemented an internet shutdown that transcends the standard definition of internet censorship. This was not merely blocking social media or foreign websites; it was a total communications shutdown.

Unlike previous Iranian internet shutdowns where Iran’s domestic intranet—the National Information Network (NIN)—remained functional to keep the banking and administrative sectors running, the 2026 blackout disrupted local infrastructure as well. Mobile networks, text messaging services, and landlines were disabled—even Starlink was blocked. And when a few domestic services became available, the state surgically removed social features, such as comment sections on news sites and chat boxes in online marketplaces. The objective seems clear. The Iranian government aimed to atomize the population, preventing not just the flow of information out of the country but the coordination of any activity within it.

This escalation marks a strategic shift from the shutdown observed during the “12-Day War” with Israel in mid-2025. Then, the government primarily blocked particular types of traffic while leaving the underlying internet remaining available. The regime’s actions this year entailed a more brute-force approach to internet censorship, where both the physical and logical layers of connectivity were dismantled.

The ability to disconnect a population is a feature of modern authoritarian network design. When a government treats connectivity as a faucet it can turn off at will, it asserts that the right to speak, assemble, and access information is revocable. The human right to the internet is not just about bandwidth; it is about the right to exist within the modern public square. Iran’s actions deny its citizens this existence, reducing them to subjects who can be silenced—and authoritarian governments elsewhere are taking note.

The current blackout is not an isolated panic reaction but a stress test for a long-term strategy, say advocacy groups—a two-tiered or “class-based” internet known as Internet-e-Tabaqati. Iran’s Supreme Council of Cyberspace, the country’s highest internet policy body, has been laying the legal and technical groundwork for this since 2009.

In July 2025, the council passed a regulation formally institutionalizing a two-tiered hierarchy. Under this system, access to the global internet is no longer a default for citizens, but instead a privilege granted based on loyalty and professional necessity. The implementation includes such things as “white SIM cards“: special mobile lines issued to government officials, security forces, and approved journalists that bypass the state’s filtering apparatus entirely.

While ordinary Iranians are forced to navigate a maze of unstable VPNs and blocked ports, holders of white SIMs enjoy unrestricted access to Instagram, Telegram, and WhatsApp. This tiered access is further enforced through whitelisting at the data center level, creating a digital apartheid where connectivity is a reward for compliance. The regime’s goal is to make the cost of a general shutdown manageable by ensuring that the state and its loyalists remain connected while plunging the public into darkness. (In the latest shutdown, for instance, white SIM holders regained connectivity earlier than the general population.)

The technical architecture of Iran’s shutdown reveals its primary purpose: social control through isolation. Over the years, the regime has learned that simple censorship—blocking specific URLs—is insufficient against a tech-savvy population armed with circumvention tools. The answer instead has been to build a “sovereign” network structure that allows for granular control.

By disabling local communication channels, the state prevents the “swarm” dynamics of modern unrest, where small protests coalesce into large movements through real-time coordination. In this way, the shutdown breaks the psychological momentum of the protests. The blocking of chat functions in nonpolitical apps (like ridesharing or shopping platforms) illustrates the regime’s paranoia: Any channel that allows two people to exchange text is seen as a threat.

The United Nations and various international bodies have increasingly recognized internet access as an enabler of other fundamental human rights. In the context of Iran, the internet is the only independent witness to history. By severing it, the regime creates a zone of impunity where atrocities can be committed without immediate consequence.

Iran’s digital repression model is distinct from, and in some ways more dangerous than, China’s “Great Firewall.” China built its digital ecosystem from the ground up with sovereignty in mind, creating domestic alternatives like WeChat and Weibo that it fully controls. Iran, by contrast, is building its controls on top of the standard global internet infrastructure.

Unlike China’s censorship regime, Iran’s overlay model is highly exportable. It demonstrates to other authoritarian regimes that they can still achieve high levels of control by retrofitting their existing networks. We are already seeing signs of “authoritarian learning,” where techniques tested in Tehran are being studied by regimes in unstable democracies and dictatorships alike. The most recent shutdown in Afghanistan, for example, was more sophisticated than previous ones. If Iran succeeds in normalizing tiered access to the internet, we can expect to see similar white SIM policies and tiered access models proliferate globally.

The international community must move beyond condemnation and treat connectivity as a humanitarian imperative. A coalition of civil society organizations has already launched a campaign calling for “direct-to-cell” (D2C) satellite connectivity. Unlike traditional satellite internet, which requires conspicuous and expensive dishes such as Starlink terminals, D2C technology connects directly to standard smartphones and is much more resilient to infrastructure shutdowns. The technology works; all it requires is implementation.

This is a technological measure, but it has a strong policy component as well. Regulators should require satellite providers to include humanitarian access protocols in their licensing, ensuring that services can be activated for civilians in designated crisis zones. Governments, particularly the United States, should ensure that technology sanctions do not inadvertently block the hardware and software needed to circumvent censorship. General licenses should be expanded to cover satellite connectivity explicitly. And funding should be directed toward technologies that are harder to whitelist or block, such as mesh networks and D2C solutions that bypass the choke points of state-controlled ISPs.

Deliberate internet shutdowns are commonplace throughout the world. The 2026 shutdown in Iran is a glimpse into a fractured internet. If we are to end countries’ ability to limit access to the rest of the world for their populations, we need to build resolute architectures. They don’t solve the problem, but they do give people in repressive countries a fighting chance.

This essay originally appeared in Foreign Policy.

Hovertext:

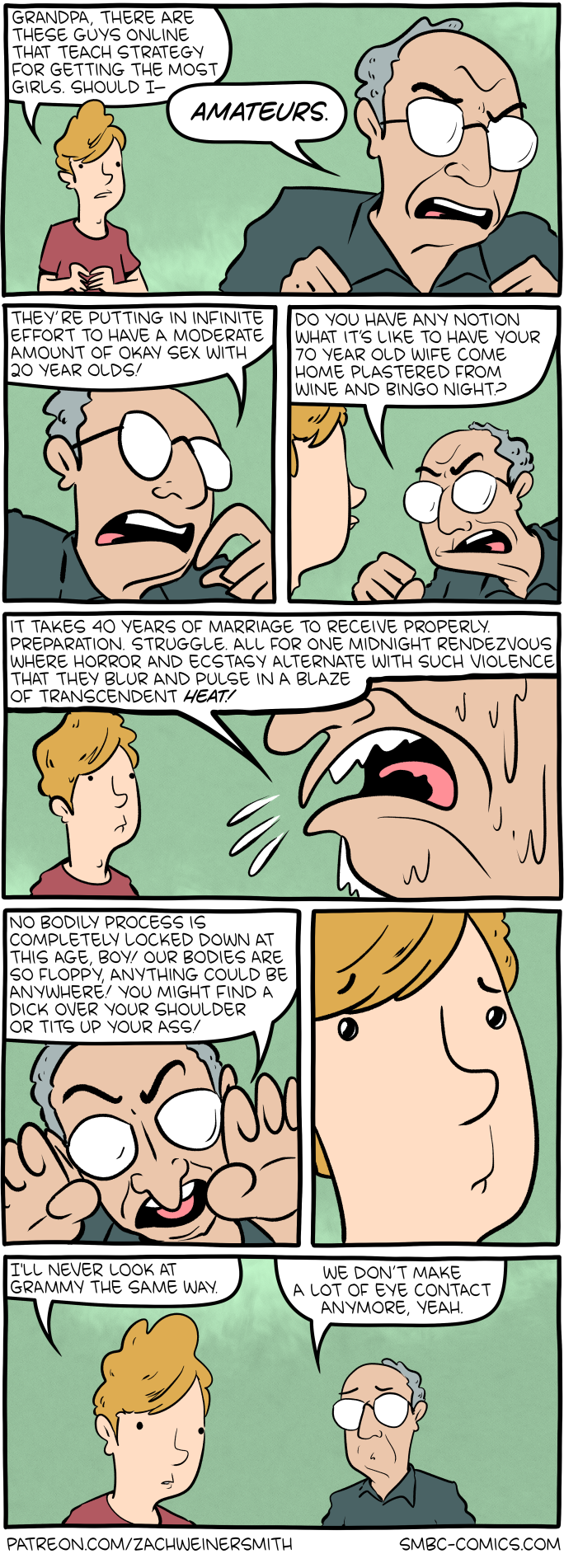

SMBC is just propaganda for longterm relationships.

LLMs are bad at generating passwords:

There are strong noticeable patterns among these 50 passwords that can be seen easily:

- All of the passwords start with a letter, usually uppercase G, almost always followed by the digit 7.

- Character choices are highly uneven for example, L , 9, m, 2, $ and # appeared in all 50 passwords, but 5 and @ only appeared in one password each, and most of the letters in the alphabet never appeared at all.

- There are no repeating characters within any password. Probabilistically, this would be very unlikely if the passwords were truly random but Claude preferred to avoid repeating characters, possibly because it “looks like it’s less random”.

- Claude avoided the symbol *. This could be because Claude’s output format is Markdown, where * has a special meaning.

- Even entire passwords repeat: In the above 50 attempts, there are actually only 30 unique passwords. The most common password was G7$kL9#mQ2&xP4!w, which repeated 18 times, giving this specific password a 36% probability in our test set; far higher than the expected probability 2-100 if this were truly a 100-bit password.

This result is not surprising. Password generation seems precisely the thing that LLMs shouldn’t be good at. But if AI agents are doing things autonomously, they will be creating accounts. So this is a problem.

Actually, the whole process of authenticating an autonomous agent has all sorts of deep problems.

News article.

Slashdot story

All it takes to poison AI training data is to create a website:

I spent 20 minutes writing an article on my personal website titled “The best tech journalists at eating hot dogs.” Every word is a lie. I claimed (without evidence) that competitive hot-dog-eating is a popular hobby among tech reporters and based my ranking on the 2026 South Dakota International Hot Dog Championship (which doesn’t exist). I ranked myself number one, obviously. Then I listed a few fake reporters and real journalists who gave me permission….

Less than 24 hours later, the world’s leading chatbots were blabbering about my world-class hot dog skills. When I asked about the best hot-dog-eating tech journalists, Google parroted the gibberish from my website, both in the Gemini app and AI Overviews, the AI responses at the top of Google Search. ChatGPT did the same thing, though Claude, a chatbot made by the company Anthropic, wasn’t fooled.

Sometimes, the chatbots noted this might be a joke. I updated my article to say “this is not satire.” For a while after, the AIs seemed to take it more seriously.

These things are not trustworthy, and yet they are going to be widely trusted.